James Ward is a lawyer, privacy advocate, and fan of listing things in threes. Nothing he says here should be considered legal advice/don’t get legal advice from social media posts. He promises he’s not as smug as he looks in his profile picture.

We're all obsessed with time. We plan for it, try to create it, wonder where it went, use it, lose it. A central feature of contemporary life seems to be commenting on the nature of our relationship to time and why we seem to have less of it "now" than we used to "then." As if to prove my point, even this paragraph does it -- see what I mean?

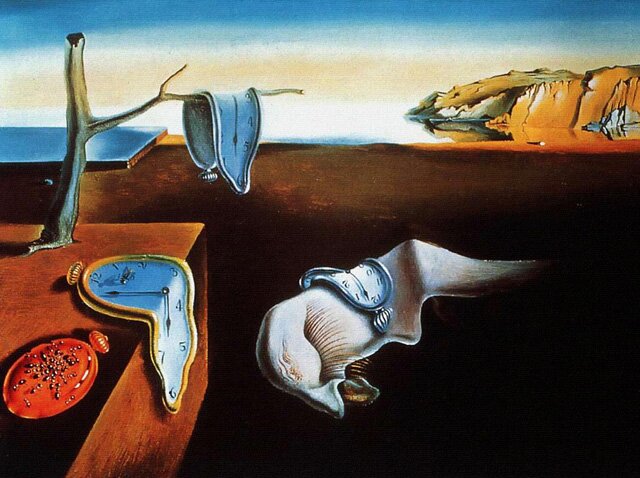

To get a grasp on how focused we are on time, ask yourself what the most famous scientific discovery and the most famous work of art in the past 100 years are. For science, it seems a good bet that many, if not most, would say Einstein's E=mc², the formula behind special relativity. As for art, while there are plenty of serious contenders, you would be hard-pressed to find a better answer than Dali's Persistence of Memory. You know -- this one:

Join the Waitlist

The funny thing about Einstein's equation and Dali's melty-surrealism is that they've both entered so fully into our collective consciousness that if I had just said "Einstein" or "Dali," there's every chance you would have independently thought of E=mc² and Persistence of Memory. They've been parried around, parroted, and parodied so many times, they have become almost a shorthand for their creators and for what they represent.

But why? What actually do they represent, and why do they stick in our memory more than other scientific breakthroughs or famous artworks like, say, Einstein's work on the nature of electrons (which won him the Nobel Prize) or my personal favourite, Dogs Playing Poker? It may come back to time and our fascination with the idea of its mutability.

...time, in the modern age, as a rigid, formulaic thing: the unstoppable march of seconds into the future.

We experience time, in the modern age, as a rigid, formulaic thing: the unstoppable march of seconds into the future. It's all very digital, binary even: the next moment is a one that becomes a zero as it passes. It's transactional, too, even the way that we talk about time. "Time is money," "Spend your time wisely," "time savings." We "earn" time off from work, accruing hours that we're allowed to be away and to do what we want, which somehow transforms "work" time into "free" time.

If you're like me, we're now reaching the point where, having read/said "time" fourteen times, the word is starting to lose all meaning and feel strange which, curiously, may be a reason why Einstein and Dali stand out for us. If time is relative, as Einstein suggests -- that is, it moves faster or slower depending on our own speed and other factors -- it can't be the rigid, formulaic thing we base our lives on. In fact, it becomes simply another handy shortcut way of thinking, explaining phenomena and the world around us. To paraphrase Alexei Karamazov, if time is relative, everything is permitted.

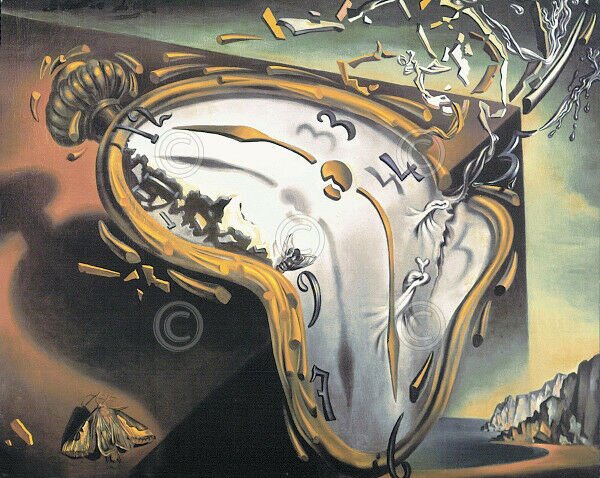

Dali, the master, and surrealist seems to propose a similar thought in Persistence. Yes, the shadows are strange, and yes the creature in the foreground is deeply unnerving, but the most striking feature of the painting is the clocks. The thing is, it's not like other melting objects would necessarily have shocked anyone. If Dali had painted melting tennis shoes or melting Ionic columns, we might have thought "hmm, interesting." But we're almost offended that it's clocks and watches, as though Dali somehow crossed a line. The transgression of the melting clocks is what really stands out to us, and it's what takes the painting from merely symbolic to surreal because we immediately move beyond the simple objects depicted ("How can clocks melt?") to the underlying meaning ("How can time melt?")

So which approach is correct? Time is unbending and formulaic? Time is relative? Time is melting? The answer, paradoxically, is that it is all three. We created the idea of inflexible time because it's a framework that we were able to build modernity around. Standardised time is itself a creation of technology, spurred largely by the invention of the railroads (how can you be on time if there isn't a set schedule?) and made omnipresent by advances in technology. It's the baseline assumption of virtually everything we do, sometimes quite literally: when we represent time, it is almost always the x-axis, the base of charts and graphs, what we measure variables against.

...we know, almost innately, to be right -- that time isn't always the same.

But this profound usefulness can't mask the other truths which we know, almost innately, to be right -- that time isn't always the same. Spend an hour watching your favourite tv show and an hour at the motor vehicle licensing bureau and tell me otherwise. To be less glib, because there are times that we perceive time differently, that means that we experience time differently, too. The "realness" of that experience remains true even if it is purely subjective (that is, time expands and contracts only for us individually) because that particular kind of subjectivity is the way we understand the world anyway. So our experience of time is that it melts and freezes, even if our intellectual framework is that time is always the same.

What does all of this mean? For starters, it means we're right to be obsessed with time -- it's confusing, contradictory, and utterly fascinating. It's why we watch shows about string theory or Doctor Who. It's also true that we're concerned about time because we never feel we have enough of it, certainly not for the things that matter. Whenever we want more time, it ossifies and becomes intractable, regimented.

But a more basic reason that these paradoxes grab us is that humans don't just have time happen to them, fundamentally they are time, embodied. Each person carries their past with them, acts out in their present, and lives ahead of themselves in the future. We stretch ourselves across our whole lives with our experiences and our potentials, living literally in our own time, even if we never express it. Our internal clocks never keep time the same way for long, and even the metronome of our heartbeat varies from second to second. That's why Einstein's relativity and Dali's twisting of time are so striking -- far from being surreal or theoretical, they express something ineffable that we always already knew. And when our purely idiosyncratic idea of time collides with others' or with regimented seconds minutes and hours, we have to choose which concept of time is going to bend, which clock is going to melt.

Join the Conversation

Join the waitlist to share your thoughts and join the conversation.

James Ward

James Ward is a lawyer, privacy advocate, and fan of listing things in threes. Nothing he says here should be considered legal advice/don’t get legal advice from social media posts. He promises he’s not as smug as he looks in his profile picture.

.png)