James Ward is a lawyer, privacy advocate, and fan of listing things in threes. Nothing he says here should be considered legal advice/don’t get legal advice from social media posts. He promises he’s not as smug as he looks in his profile picture.

As we reach the third week of the war in Ukraine, commentators around the world are turning their attention to China and its response to the invasion. Although the initial consensus was that China would likely attempt to play a mediating role in the conflict, that hasn’t proven to be the case. Instead, over the course of the last three weeks, we’ve seen an escalation of rhetoric and, in some cases, acts demonstrating China’s non-neutral role in events. What began as abstentions in the U.N. Security Council votes about the invasion have morphed into economic and propaganda efforts from Beijing that signal, if not outright support, then tacit approval for Russia’s conduct.

Why, given the nearly universal opprobrium for Putin’s war in Ukraine, is China following this course? Under the circumstances, it would be hard not to interpret China’s approach to the Ukraine war as one of hedged support for their northern ally. But that only raises the secondary question: why? And looming behind all of this is the next question of how China’s expressed, long-term goal of bringing Taiwan to heel survives unchanged in the wake of a coordinated Western response to Russia’s conduct.

Dragon and Bear

Join the Waitlist

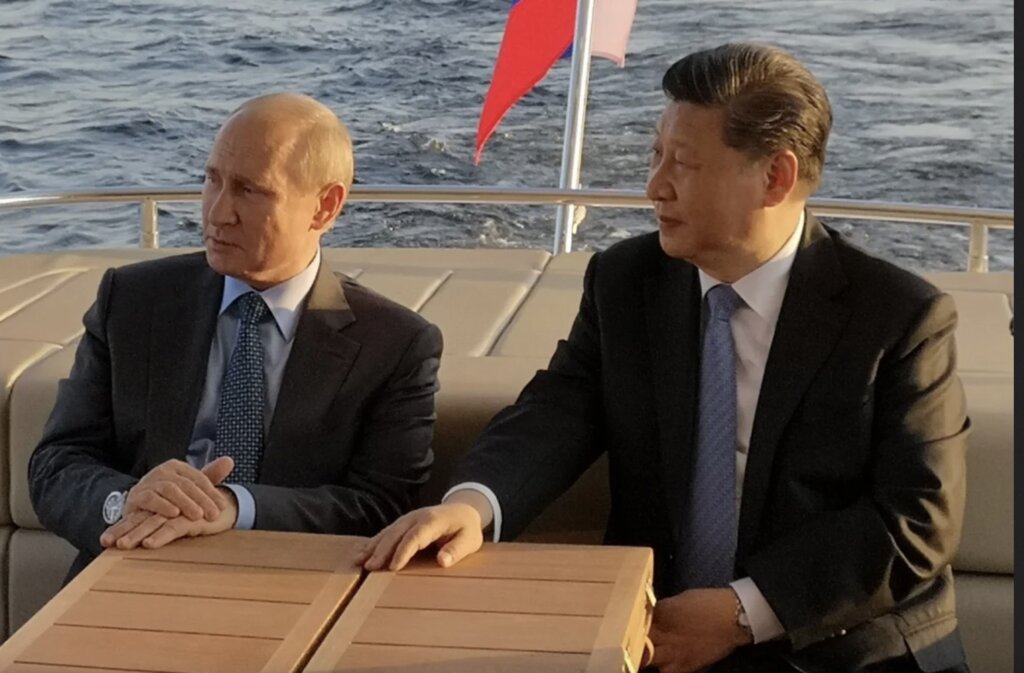

The first principle to bear in mind here is that China does not act out of some sense of fraternal obligation to Russia or based upon the putative friendship between Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin. That kind of pop psychobabble approach to foreign policy always crops up in times of crisis, but it is of little to no value. Xi’s China is no different than Putin’s Russia in that neither would hesitate to challenge the other if their interests directly conflicted. The goal of their alliance — which they called “limitless” just weeks before the war in Ukraine began — is a mutually-reinforcing bloc of a sixth of the world’s population, a fifth of the world’s land area, and most of its nukes. This alliance brings immediate benefits to Russia. China will buy Russian natural gas and oil (as it does now) and is making moves to ease the isolation of the ruble. Chinese goods will continue to flow into Russia, and there has even been talk of military hardware sales, though whether they materialise remains to be seen.

And what does China get? It’s complicated, but a secure northern border, a friendly voice in international fora like the U.N., and an unquestionably open market for goods and the yuan. There’s also the thought that a United States bogged down in defending Europe is less capable of the long-awaited “shift to Asia” aimed at curtailing Chinese ambitions in the region. This is realpolitik in its most basic form, or perhaps the Kissingen Diktat: when there are three great powers, always be on the side that has two of them.

But sometimes, the price of having a partner is too high, and China may be on the cusp of learning this lesson. While there have been rumblings around China being the “winner” of this war (setting aside the fact that China is a noncombatant in a war that has barely begun), I think the balance of factors goes in another direction. Even the supposed successes for Beijing have been little more than symbolic: contrary to the stories in the press, Saudi Arabia has not authorised the purchase of petroleum in yuan instead of the dollar, and rumours of the death of American dominance in the Middle East are greatly exaggerated.

In fact, matters seem to have gone a very different direction for China and could turn out to be a major crisis for Xi. Here are two reasons why.

China Does Not Seem Like a Seasoned Diplomatic Power

Soft power is a hard thing to acquire and a harder thing to keep. Throughout the course of the Belt and Road Initiative, Chinese efforts have centred upon the idea that Beijing is the pole of a new axis of global power and that developing economies have a better chance of success turning away from Washington and Brussels. That story has already come under pressure given the usurious terms of many of the B&R loans and development schemes, but it could still have some merit given China’s relatively neutral posture on most global conflicts.

That’s over now. The Russian invasion doesn’t leave much room for ambiguity: either it was an illegal act that violated Ukraine’s sovereignty, or it was… whatever Russia’s newest explanation is. China’s statements on the matter confirm this, in that they are full of hedges and what lawyers call “precatory language” about hoping things work out.

“We will continue to monitor the developments of the situation closely and call on relevant parties to keep calm and exercise restraint, prevent further escalation of the situation and ensure the safety of relevant nuclear facilities.”

China wants to play a primary role in the international community, but this statement comes across as pandering to Russia’s interests while nodding towards global concerns. That’s not a great strategy for building a global diplomatic profile, and the diaphanous claim that nuclear security is China’s top priority makes the entire statement seem almost unserious. And that is a major problem on a diplomatic level — you can always be cynical, you must never appear cynical, and right now, China does.

Europe Looks East, and So Does the United States

American politicians have been talking about a shift to an “Asia First” foreign policy for the better part of two decades. After the Cold War ended, the idea was that American strategic goals originated in Asia — containment of China, ensuring Taiwan’s autonomy, secure supply chains, isolation of North Korea — and that Europe could fend for itself. Indeed, a centrepiece of the 2012 U.S. Presidential election was the Obama campaign’s insistence that redeploying American forces to the East was the only rational choice and that Mitt Romney’s concerns about Russia were just the “1980s call[ing] to ask for its foreign policy back.”

Some of the initial hot takes on the invasion relied on the assumption that a resurgent (or at least increasingly aggressive) Russia would divert American attention from Asia. To be fair, that thinking was a reasonable interpretation of the US-China dynamic, ceteris paribus. But all other things are not equal. Germany’s pledge to rearm and meet the NATO 2% defence spending target (under a Socialist Party government!), mass popular support for the Atlantic Alliance, Swedish and Finnish bullishness on Washington, terminating the Nordstream 2 pipeline, and the near unanimity about severe sanctions on Russia were unanticipated, even unthinkable as recently as January.

These factors matter because, if they endure, they will free up American resources. What’s more, Russia’s war has accelerated calls for increased defence spending in South Korea and Japan and a surge of pro-American sentiment in the political classes. And while India and Saudi Arabia have been hesitant to criticise Putin or hew close to the line from Washington and Brussels, no one seriously expects a realignment of either country towards Beijing, given that India has a highly complex relationship with China and that Saudi Arabia depends on the U.S. military for security.

Reading Tea Leaves

Does any of this mean that China is certain to lose face or standing as a result of its (so-far) tepid support for the invasion of Ukraine? No. The war is at too early a stage, and there are too many factors at play to make that kind of prediction with any sense of security. The better question is what indications will China give that it recognises these risks and wants to avert them? One key indicator for China is always what’s being said at the think tanks and universities. Whilst the official press is always touting the party line, prominent academics often float ideas in order to gauge how they’ll be received in the West. It’s a subtler, second-tier kind of diplomacy, but it has its merits.

That makes some of the recent press all the more telling. Just read what a research fellow at the Chinese Institutes for Contemporary International Relations (CICIR), the top Chinese foreign affairs think tank, had to say only yesterday:

While the U.S. has spared no effort to exert diplomatic pressure on China to join the sanctions against Russia, it has consistently smeared both China and Russia in the international public opinion space, stirred up troubles on the Taiwan question and continued to hype China as the No. 1 strategic threat to the West. This is evidence that the U.S. hopes to use the crisis to strengthen Europe’s strategic dependence on the U.S. and turn Western solidarity into a strategic containment force against China.

CICIR is effectively administered by the Chinese intelligence services and is overseen by the Central Committee, which means its statements are akin to a glimpse into official thinking. And what do we see? A tacit acknowledgement that Western unity about Ukraine could lead to a reassertion of American leadership in Europe and the beginnings of the shift to an Asia-first policy. There have been a variety of similarly-themed articles, but some, too, that suggest that support for Russia has been a strategic error for China, and that the reputational hazards couldn’t be higher.

...you can always be cynical, you must never appear cynical, and right now, China does.

The effects of the war in Ukraine for China remain indeterminate, but the risks are palpable. Without opting for a clear pro- or anti-invasion stance, China risks alienating the world while simultaneously doing little to help the Russian war effort. Moreover, as Russian isolation deepens, pouring money, resources, and cachet into the Moscow-Beijing relationship risks becoming a client state relationship, with the risk of an unstable, nuclear-armed pariah state on the northern border.

Palmerston said that nation-states “have no eternal allies and no perpetual enemies . . . [only] interests are eternal and perpetual.” Despite promises of a Sino-Russo “friendship with no limits,” the Ukraine war may soon reveal what happens when a temporary ally threatens a perpetual interest.

Join the Conversation

Join the waitlist to share your thoughts and join the conversation.

James Ward

James Ward is a lawyer, privacy advocate, and fan of listing things in threes. Nothing he says here should be considered legal advice/don’t get legal advice from social media posts. He promises he’s not as smug as he looks in his profile picture.

.png)